Why You Need an Ontology (Schema.org, JSON-LD and ElasticSearch - Part 1)

ElasticSearch is great place to store JSON, not just because it’s a JSON store like MongoDB, but because it brings with it powerful search and analytics. To get the most out of storing our data in ElasticSearch we need to think through features such as field names, data types and the relationships between different parts of our data. If we get this structure right then we’ll increase the opportunities for comparing different kinds of data and for generating new information. We’ll also make it easier for people within our organisation to know where to find things. And as a bonus, these mappings will help ElasticSearch to store our information more efficiently.

This article is the first of a short series that looks at how to get from modelling data to ElasticSearch mappings, by way of Schema.org and JSON-LD. This post looks at why ontologies like Schema.org are useful, whilst the next post looks at how to use Schema.org to represent data as a set of events on a timeline. The third post looks at how to model the data in JSON, using JSON-LD, and then the final post discusses getting the data into ElasticSearch, looking in particular at how to set up the mappings.

Ontologies

We won’t go far wrong if we always start a project by creating some kind of ontology, by which we mean a collection of terms that identify the real things and relationships that are relevant to the area we’re interested in. The act of discussing an ontology’s design always throws up real-world issues and so helps clarify what we’re doing. At the same time keeping track of the terms – even if it’s in a simple spreadsheet – ensures that anyone getting involved in the project can quickly get up to speed.

For example, at state51 we’re dealing with concepts like musician and publisher. Either of these might sell items, like a t-shirt, a poster, or a recording, and they would sell these items to a customer. The music might be made available as a download or stream by way of a digital service like iTunes, Spotify, Google Play, or one of the many other services that state51 supports. It might also be delivered in the post in the form of a CD or on vinyl. And the purchase itself might have been made through any one of a number of websites.

Even with these few simple terms and relationships – musician, customer, download, purchase, etc. – we need to establish many related notions, such as postal addresses, currencies, refunds, albums, number of downloads, number of plays, and so on. And if we then decide to track other information that might have a bearing on sales – data that could be used for analytics and predictions – then before we know it we’re also modelling artists’ Tweets and Facebook pages, dates of live shows, press interviews, social media ‘likes’ and ‘mentions’…and maybe even the weather. All of these terms and relationships constitute our ontology.

Create a Custom Ontology or Build on the Shoulders of Giants?

There’s nothing wrong with creating our own custom ontology, and for some businesses and endeavours this will be unavoidable.

However, it’s worth taking as our starting-point that our data is often not as ‘special’ as we like to think it is, and so there may well be pre-existing ontologies that we can use. If we can use other ontologies then it will save a lot of time; we’ll save time at the beginning of a project as we reduce the discussions needed to devise a set of terms, and we’ll save time as we progress, by lowering the effort needed to maintain the documentation about these terms.

For example, each item of music that can be downloaded or streamed has a unique Global Release Identifier (GRid), which is much like the barcode that would appear on a physical product. When modelling our data we could simply add a field called ‘grid’ to our data store, put an entry in our central documentation, and then be done.

However, if we want to take this to 11 we can take a look around to see if someone has already provided a definition for a data field that represents GRid; as you’d expect, someone has, and it’s part of the extensive Music Ontology.

If we use the Music Ontology’s notion of GRid then we get for free all the thinking that lies behind defining this field, and any thinking that might require the field to change or be refined, in the future. All we have to do is to maintain a link from our documentation to the original source.

Using Ontolgy Terms as Database Field Names

To make use of this field in our data stores a simple convention would be to use the field name and a prefix; in our database we would call the field ‘mo:grid’ rather than simply ‘grid’. If the colon is a problem in the software we are using then we can adopt something else, like an underscore, and do some pre- and post-processing in our code, as necessary. For example, we might use ‘mo_grid’ as the field name in a database but still allow queries to be expressed through our user interface with ‘mo:grid’, mapping between the characters in code.

The main point is that the character used is just a convention that will allow us to use field names and definitions from a myriad of sources across the web. It’s independent of whether we’re using a relational database like MySQL, a JSON store like ElasticSearch or a column-oriented NoSQL store like HBase; this simple convention says that no matter which store we use, when we see a field called ‘mo:grid’ we know that it has all of the features and meaning of the ‘grid’ property from the Music Ontology…which by the way, defines the field like this:

The Global Release Identifier (GRid) is a system for uniquely identifying Releases of music over electronic networks (that is, online stores where you can buy music as digital files). As that it can be seen as the equivalent of the BarCode (or more correctly the GTIN) as found on physical releases of music. Like the ISRC (a code for identifying single recordings as found on releases) it was developed by the IFPI but it does not appear to be a standard of the ISO.

Schema.org

While the Music Ontology is incredibly rich there’s another ontology which may be more appropriate for many common scenarios, and that’s Schema.org. At first sight it might appear a little ‘light’, but as we dig in we’ll find that it can support many different types of information. And should it not be enough, there are also a number of ways that it can be extended.

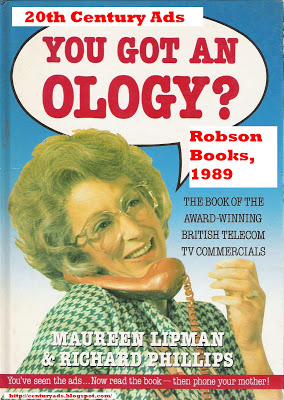

Schema.org comes with an additonal bonus over other ontologies that we might use which is that it is ‘understood’ by many search engines; if a document contains items that have been described using Schema.org then those terms will help create a better user experience when that document appears in search results:

In this example information about an album has been marked up in a web page using Schema.org, and then extracted during the search engine’s crawl. The extracted data is then used in search results to show extra features such as the ‘Listen now on Spotify’ button in the screenshot above. (More information about how this can be done is available at Google Search > Documentation > Datatypes > Music.)

Now that we’ve decided to use common property names and classes across our data stores and to use Schema.org and the Music Ontology as convenient sources of terms, we can move on to look at how we can model some real data. We’ll do that in part 2 of the series, where we model data as events in time.