Ajax and progressive browser enhancement

There is still plenty of scope for the browser to evolve, but the truth is that progressive browser enhancement makes browser evolution far less significant than it has been until now. That’s probably not a bad thing, given the chaos that is currently surrounding the development of HTML at the W3C.

Introduction

Progressive enhancement is an approach to web development that has been around for a few years now. (More on PE at Wikipedia.) At its most basic it suggests building our web pages in a ‘clean’ and uncluttered way, and then layering functionality onto the mark-up using various mechanisms, such as stylesheets and scripts. The idea is that browsers without the additional capabilities can still render the page in some fashion, but those with additional power–such as scripting support–can add more enhanced features.

This principle actually underpins much of the work we’ve been doing on XHTML 2, which has involved taking HTML back to its semantic roots. In particular the work on RDFa has been to a large extent motivated by providing more semantic ‘hooks’ on which to attach increasingly focused functionality. (The work pre-dates the term progressive enhancement, so it isn’t generally called that in our discussions of XHTML 2 or RDFa.)

But there is a new phenomena afoot, which I’d like to call progressive browser enhancement. It’s something we’ve been doing for a while with our work on XForms and formsPlayer, but it also has wider applicability.

DOM Events and standards

To illustrate the idea of PBE, let’s look at eventing in the browser. Many Ajax libraries have their own eventing architecture, and they are without exception non-standard. This is a shame, since the W3C has a standard for DOM events (DOM 2 Events) which has been around for years and is very clearly defined. Of course, part of the problem is that whilst it has been implemented in Firefox, Safari and Opera, it’s not available in Internet Explorer. This meant that when we began our work on formsPlayer, our XForms processor plug-in for Internet Explorer, we had to implement a DOM 2 Events component ourselves.

This does however mean that DOM 2 Events support is potentially available for all browsers, but of course the problem now is that in order to make use of it on IE, people would have to install formsPlayer. And even if we made the module available separately (which we will be doing shortly), the problem for the programmer is that they can’t assume that it is installed; there is still an annoying rift between those who have browsers with DOM 2 Events support, and those that don’t.

Using JavaScript to enhance the browser

To fill the gap we simply implemented a DOM 2 Events library in JavaScript. Whilst most Ajax libraries went the route of creating their own non-standard eventing architectures, we went the other way and implemented the standard. The advantage of our approach is that if our end-user is running a browser with reasonable standards support such as Firefox, Opera or Safari, they’ll get native support for DOM 2 Events, and hopefully a faster experience. Similarly, if our user is on IE and has installed the formsPlayer DOM 2 Events component, they will likewise get a faster experience. It’s only the middle group using the scripted version of DOM 2 Events who will have a slightly slower experience.

But the key point is that the end-user now has some control, since they can add a DOM 2 Event component if they want to–most likely as part of some other package–independent of the actual web applications they are using. And for the authors of web applications life is much easier, since they are coding to a standard, rather than being forced to code to the specific event architecture of YUI, Dojo, or whatever Ajax library they want to use.

This is the key idea of progressive browser enhancement.

Threading in Google Gears

Another example of PBE is threading in Google Gears. There are a number of JavaScript libraries around that create simple threading by using the timer in JavaScript. This is fine for a lot of uses but can affect performance. However, we can follow the same approach as I described above for DOM 2 Events; if the function calls that the programmer makes to create a thread are ‘standard’, then although in normal operation the less-efficient JavaScript version would be used, with no change to the code the web application can take advantage of ‘proper’ threading, should a user have Google Gears installed. (See also: Ajax makes browser choice irrelevant…but we still need standards.)

Of course, most users are unlikely to be looking for a threading library to install, just as they will not be downloading a DOM 2 Events module. But if these components are small enough to be bundled up with other pieces of software they will gradually find their way onto users machines as part of other, useful, packages.

In whatever way the distribution takes place, it’s the end-users of our web applications that are in control of progressively enhancing their browser, not the web application programmers themselves.

These principles have underpinned the design of Yowl, a centralised notification system for web applications.

Yowl centralised notification system

Yowl is a way of providing notifications to users of web applications, but in a way that the user themselves can control. It was inspired by Growl, which runs on the Mac, and which is used by applications such as Skype and Adium; by passing all notifications through a central system users are given the power to decide which messages they are interested in, and how they want to see–or even hear–them.

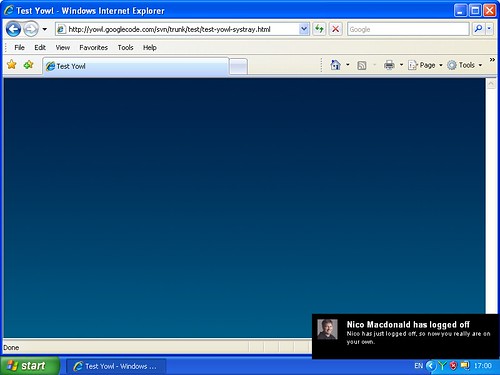

Progressive browser enhancement allows Yowl notifications to make use of advanced features in the browser if they are available, but to fall back to basic notifications if not. For example, we’ve created a Windows component that allows messages to be displayed above the system tray. The component is invoked and called from script, and works with both Firefox and Internet Explorer:

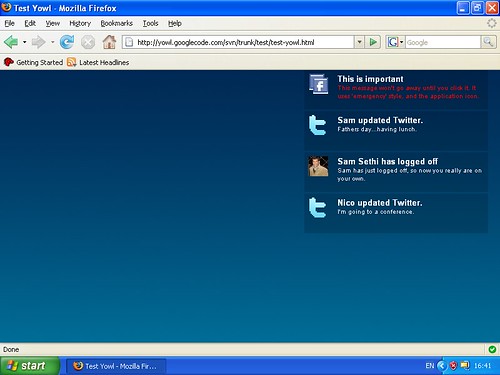

However, if the systray component is not installed, the Yowl notification system will simply use JavaScript to show messages within the browser window. You can see a sample of the non-enhanced notifications here–it will run in all the major browsers:

The programmer need change nothing in their code to make use of the systray component if it is present, since as with the DOM 2 Events example, or Google Gears and threading, the user is in control of the browser enhancement, not the programmer.

(For more on Yowl see the Yowl open source project page, Yowl: Design principles and how to use it and Yowl: An open source centralised notification system.)

Where does this leave the browser?

There is still plenty of scope for the browser to evolve and make available the kind of features we’re talking about here. But the truth is that progressive browser enhancement makes browser evolution far less significant than it has been until now. That’s probably not a bad thing, given the chaos that is currently surrounding the development of HTML since the W3C gave its support to HTML 5; the spec itself is becoming increasingly top-heavy, and bears little relationship to the early principles of HTML. Far from relying on enormous ‘kitchen-sink’ specifications, PBE looks to add new features in a more nimble way, via small and focused modules.